In the Dec. 11, 2000, issue of

The New Yorker, the magazine’s revered literary critic James Wood began his review of the writings of J. F. Powers with a blunt question, “

Does anyone, really, like priests?” I read that article a few months after my ordination to the priesthood. I found it hard to understand not only how an intelligent person could write a sentence like that, but how a prestigious magazine could print it.

It does not take too much creativity to imagine what the reaction might have been had The New Yorker’s literary critic written, “Does anyone, really, like imams?” Or “Does anyone, really, like rabbis?” Firestorms of denunciations would likely have followed. In the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, we saw a flurry of thoughtful articles distinguishing Islam from the terrorists who committed the atrocities (and the clerics who encouraged them), with commentators correctly making judicious distinctions between the actions of a few and the morality of the many.

But when it comes to priests, it is O.K. to hate them. Or at least wonder if anyone, really, likes them.

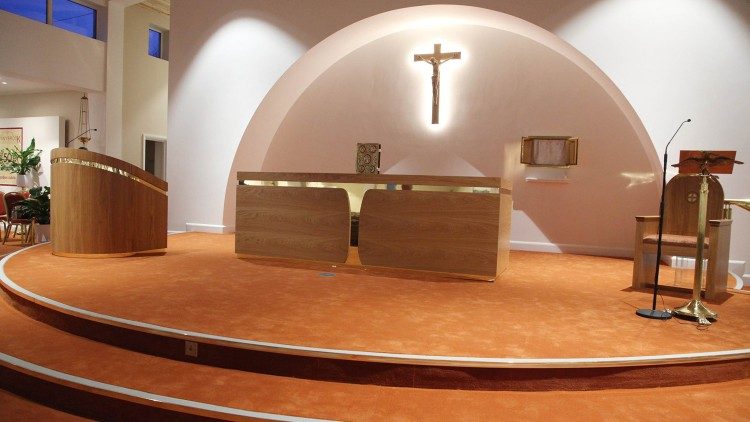

I thought of that article when I saw the cover of the latest edition of The Atlantic, which features a darkened photo of St. Patrick’s Cathedral above the headline, “

Abolish the Priesthood.”

Mr. Carroll, an astute social critic and often brilliant writer, should know better. The problem is not the priesthood; the problem is clericalism, that malign brand of theology and spirituality that says that priests are more important than laypeople, that a priest’s or bishop’s word is more trustworthy than that of victims (or victims’ parents) and that the very selves of priests are more valuable than those of laypeople. Catholic theology is sometimes used to support this kind of supremacism. At his ordination a priest is said to undergo an “ontological” change, a change in his very being. The belief that this change makes him “better” than the layperson lies at the heart of clericalism and much of the abuse crisis.

On this, then, I would agree completely with Mr. Carroll, who knows his theology. And I certainly understand his anger and anguish over the abuse crisis, which I share. The problem, however, is that his article consistently conflates the priesthood with clericalism. Basically, he is engaging in a stereotype. In short, not all priests are “clerical.” Not even most of them.

Let’s step back and look at other places where sexual abuse happens, as a way of understanding the flawed logic that mars The Atlantic piece. Most abuse happens,

say experts, within the context of families: fathers (and stepfathers) preying on children and adolescents, to take one example. The reasons for abuse by fathers (and stepfathers), as with priest abusers, are complex.

But few people ever suggest that either marriage or the family are bankrupt institutions or that we should “abolish fatherhood.” Why not? Because most people understand that abusive fathers (and mothers for that matter) are in the minority. Most people know many good and caring parents (and stepparents) who have never and will never abuse anyone. And so we avoid lazy stereotyping.

The same is true with schools. Sexual abuse in the public-school system (as well as in private schools) has been

well documented. Some cases are as appalling as those that happened within the church. Yet despite many incidents of sexual abuse perpetrated by teachers, counselors and coaches, few people say “abolish public schools” (that is, the “system” that gave rise to the cases of abuse). Or “abolish the teaching profession.” Again, this is because we avoid stereotyping.

Except when it comes to Catholic priests.

Mr. Carroll also takes aim, as he often does in his articles and books, at celibacy. But this is another red herring. If celibacy were the underlying issue, and if celibacy leads to abuse, then we should suspect every unmarried aunt and uncle, every single brother and sister, and every widow and widower of being an abuser. Does a person instantly become a child molester if he or she begins living a celibate lifestyle?

At the heart of many of Mr. Carroll’s articles on the Catholic Church, especially those written as a columnist for The Boston Globe at the height of the sex abuse crisis, is his own history as a priest. In The Atlantic, he writes, “If I had stayed a priest, I see now, my faith, such as it was, would have been corrupted.”

Would it have? I can’t answer for Mr. Carroll and want to give him the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps it would have. I have no idea. But this does not mean that staying in the priesthood corrupts all priests. Or most. Or even many. His article nods to “good priests” here and there, speaking of the church as the “largest non-governmental organization on the planet, through which selfless men and women care for the poor, teach the unlettered, heal the sick and work to preserve minimal standards for the common good.”

Including priests. Bluntly put, if 5 percent of Catholic priests are abusers, then 95 percent are not. (The numbers, by the way, are actually lower for priests than for

men in general.) In the midst of this hateful, corrupt, misogynistic system, as this article describes it, how do we account for the good priests? For Father Mychal Judge, Father Henri Nouwen, Father Greg Boyle, Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Farther back, for Father Ignatius Loyola, Father Francis de Sales, Father Vincent de Paul. One of Mr. Carroll’s heroes is St. John XXIII. Also known as Father Angelo Roncalli.

Need I go on? Maybe I should. Maybe I should list a few hundred good and holy priests, or a few thousand, or a few hundred thousand. But I wonder if even a long list would do any good these days. Because, basically, it’s okay to blame all priests, and the priesthood in general, for the abuse crisis. Instead, let’s ask a question I have long wanted to pose to Mr. Wood and now to Mr. Carroll: Does stirring up contempt against priests do much good? Does that,help us confront the sex abuse crisis?

Or does it, really, just make people hate more?